|

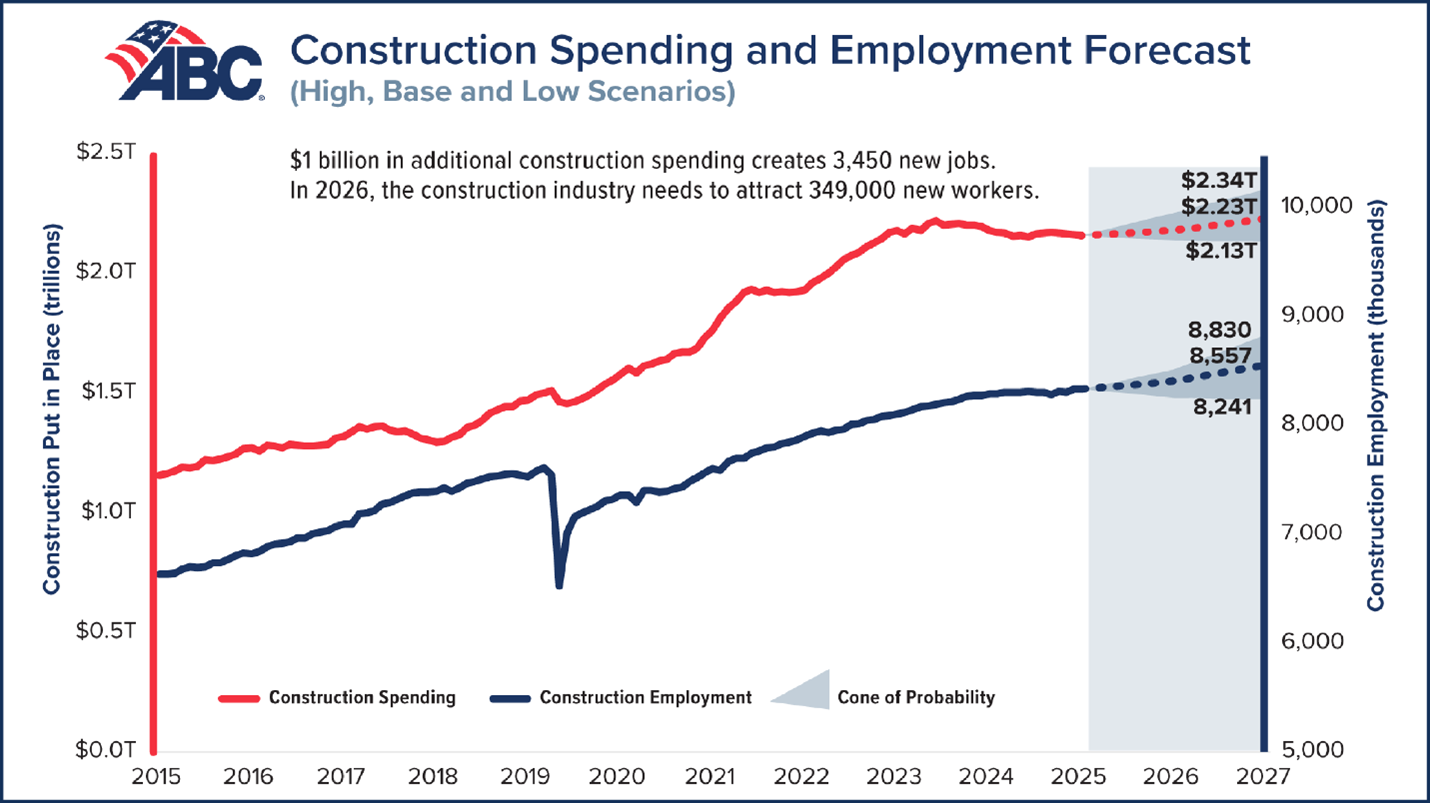

The construction industry needs to attract an estimated 349,000 net new workers in 2026 to meet demand for construction services, according to a proprietary model developed by Associated Builders and Contractors. In 2027, the industry will need to bring in 456,000 new workers to meet demand as construction spending growth is poised to resume for the first time in years.

ABC’s proprietary model uses the historical relationship between inflation-adjusted construction spending growth, sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Construction Put in Place survey, and payroll construction employment, sourced from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, to convert anticipated increases in construction outlays into additional demand for construction workers at a rate of approximately 3,450 jobs per $1 billion in additional construction spending. This model also embeds the current level of job openings, industry unemployment and projected industry retirements into its computations.

“If current consensus forecasts hold true, the construction industry will need to bring in 349,000 new workers in 2026 just to keep the supply and demand for labor in equilibrium,” said ABC Chief Economist Anirban Basu. “Failing to do so will worsen labor shortages, especially in certain occupations and regions, placing further upward pressure on labor costs.

“The industry needs to attract fewer workers than in recent years, a decline that can be traced to extremely modest spending growth forecasts for 2026 and 2027,” said Basu. “Given current assumptions regarding prospective industry growth, a majority of new worker demand in 2026 will be attributable to retirement rather than increased demand for construction services, despite the ongoing boom in artificial intelligence infrastructure buildout.

“The industry will need even more workers than the model predicts should current spending projections prove overly conservative,” said Basu. “That is a distinct possibility, especially if project financing costs decline unexpectedly or if lingering policy uncertainty resolves itself quickly and favorably. It is also important to note that nonresidential specialty trade contractors have added 95,000 jobs since August 2024, according to ABC analysis of BLS employment data, demonstrating that certain sectors of nonresidential construction hiring are going strong.”

“ABC’s 2026 workforce shortage analysis shows a series of macrodynamics at play in the industry,” said Michael Bellaman, ABC president and CEO. “These include an aging and retiring workforce, immigration enforcement, high materials prices, tariffs, office vacancies and rapidly evolving technologies and innovation. Despite these variables, the analysis shows the construction industry still faces an urgent need for talent to build and rebuild America’s infrastructure.”

“Even if construction spending fails to exceed expectations this year and next, contractors will continue to struggle to fill open positions, especially in certain occupations and regions,” said Basu. “For instance, demand for electricians capable of precision wiring has surged due to the rapid increase in data center construction. Recent industry efforts to accelerate skilled worker development have helped, but the industry is effectively swimming upstream. Approximately one-fifth of all electricians are over 55. Worker shortages also remain more severe in areas associated with industrial megaprojects, including semiconductor fabrication facilities.

“The effects of immigration policy represent another potential wildcard for the industry’s labor force dynamics,” said Basu. “While the extent to which undocumented workers have exited the workforce remains unclear, data regarding border encounters indicate that the flow of undocumented workers into the country fell precipitously in 2025 while voluntary deportations accelerated.”

“This slight dip in the industry’s chronic, massive worker shortage offers practical lessons,” said Bellaman. “These include federal lawmakers introducing a market-based worker visa system; reskilling and upskilling workers on new tech and innovation; and deploying ABC’s all-of-the-above workforce development strategy to bring new workers into the industry and educate them through both industry-driven and government-registered apprenticeship programs.

“The construction industry does not have to fall off the workforce shortage cliff,” said Bellaman. “To avoid this outcome and shore up the talent pipeline, now is the time for action—not complacency—to reaffirm that the construction industry offers careers of choice in today's complex job market.”

|